Church

| St Nicholas Church, Leicester | |

|---|---|

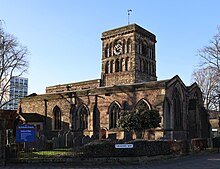

St Nicholas from the south west and the Jewry Wall St Nicholas from the south west and the Jewry Wall | |

| 52°38′6.53″N 1°8′27.29″W / 52.6351472°N 1.1409139°W / 52.6351472; -1.1409139 | |

| Denomination | Church of England |

| Previous denomination | Roman Catholic Church |

| Churchmanship | Broad Church / Modern Catholic |

| Website | www.stnicholasleicester.com |

| History | |

| Founded | Before 879 AD |

| Dedication | Saint Nicholas |

| Architecture | |

| Style | Anglo-Saxon, Early English, & neo-Gothic |

| Years built | 9th - 19th centuries |

| Administration | |

| Province | Canterbury |

| Diocese | Leicester |

| Archdeaconry | Leicester |

| Clergy | |

| Bishop(s) | Martyn Snow |

| Curate(s) | The Revd Canon Karen Rooms |

550yds

St Nicholas Church, often known informally by locals as Holy Bones, is an ancient Anglo-Saxon Church of England parish church in Leicester, England. First mentioned in 879 AD, the core of the structure is over 1150 years old making it the oldest of the five surviving medieval parish churches in Leicester City Centre, Leicester's oldest place of worship, its oldest complete building, and its longest continually used building.

The building is located on the western edge of Leicester City Centre between Holy Bones to the north, Vaughan Way and Jubilee Square to the east, St Nicholas Circle to the south, and the ruined Jewry Wall, Roman bath complex, and Jewry Wall Museum to the north. It was built as the minster for the Anglo-Saxon Bishops of Leicester (9th century), added to following the Danish invasion (10th century), the Norman Conquest (11th century), during the High Middle Ages (12th century), and completed in the Victorian period (19th century). It is a Grade I listed building.

Today, St Nicholas attracts an active and predominantly young congregation. It is the official church of the University of Leicester. It is the cities evening congregation, with the principle Sunday mass held at 6.30pm. The parish community is in the Broad, Catholic, and Progressive traditions of the Church of England. It is also a prominent member of the Inclusive Church Network.

History

The site in Roman times

Located adjacent to the Jewry Wall, the church sits in the centre of the ancient Roman city of Ratae Corieltauvorum. Numerous ideas about the use of the site in Roman times have been circulated, the most popular being that it was a temple of the god Janus. This idea arose from the discovery of many historical animal bones scattered around the site which were assumed to be evidence of ancient sacrifice. These also gave rise to the name of the adjacent street name, Holy Bones, and the subsequent nickname for the church. Other antiquarians speculated that the site was a Basilica, the Decumanus Maximus (principal street running east to west) opening out of the Jewry Wall which it was assumed was the west gate of the city.

Present archeology suggests the site was most likely a courtyard between two gymnasia and that the Jewry Wall was the entrance into the adjacent bath complex which today lies exposed by archeologists to the west of the churchyard. Ratae's Forum lay immediately to the east of the church and vestiges of masonry from its colonnade still litter St Nicholas' churchyard today. The abundance of readily available second hand building materials, the prestige of the sites Romanitas, and the central location in the settlement were probably the reason it was selected by the Anglo-Saxons for constructing a church.

Anglo-Saxon minster

Leicester gradually converted to Christianity after St Cedd's mission to the Middle Angles of 653 AD and St Chad’s missions to the Mercians of 669 AD. At first the borough was administered from Lichfield by St Chad, however, by 679 Leicester had its own bishop, Cuthwine. St Nicholas was almost certainly the site of the cathedral or minster of the ancient bishops and the north wall of the nave was probably constructed under the auspices of one of Cuthwine's successors, perhaps incorporating the Jewry Wall as its west front. St Margaret's, located in a Roman cemetery outside the north east corner of the city walls, also has Anglo-Saxon foundations and has been suggested as a candidate for the cathedral however this is not the consensus.

The structure was rebuilt at least once during its early life. The date of the current double bayed nave is disputed. Both the official listing and the parish guidebook cautiously date it to 879 AD when the Danish invaders record the presence of a minster. The Victoria County History authors are more bold and suggest a dating any time between the 740s and 879 is not unreasonable. Whatever its date, the structure likely had a semicircular apse on the site of what is now the tower.

During the Danelaw

In 879 AD, Leicester was overwhelmed by Danish invaders and became part of the Danelaw. At this point Ceobred, last of the ancient Bishops of Leicester, fled his seat. His bishopric was passed on and soon reestablished his far away in the south in Dorchester where it remained until the Norman conquest before being returned to the Midlands and installed at Lincoln (see Bishop of Lincoln). As mentioned, this is the first time the existence of a minster at Leicester appears in surviving records as the Anglo-Saxon chronicles merely record the names of the bishops without mentioning their church.

In the 10th century (900s AD), the single nave basilica was added to by the construction of the lower sections of the surviving tower and two transept chapels. The basilical structure thus took on the form of a cross with the alter probably sitting in a reconstructed apse behind the eastern arch of the tower on the site of the present chancel. These developments probable followed the 918 reconquest of Leicester by Anglo Saxon forces under Ethelfleda, Lady of the Mercians, and Edward the Elder, both children of Alfred the Great. They were also responsible for the reconstruction of the towns walls, and the first church on the site of St Mary de Castro.

It is probable that either the nave or churchyard, or both depending on weather, were the meeting place of the Jurats of the Moot of Burgesses, the central committee of the government of the ancient borough of Leicester. It is these meetings of the Jurats that gave the adjacent Jewry Wall its name. This is recorded after the conquest from documents in the 12th century but may well have predated 1066.

Medieval parish church

After the Norman Conquest the church became a parish in the Diocese of Lincoln. At the time of the Doomsday Survey the advowson of St Nicholas was in the possession of either the Bishop of Lincoln or the Lord of Leicester, Hugh de Grandmesnil. Although a tiny parish (less than 16 acres in size), in the early medieval times it was at the heart of commercial activity in Leicester sitting on the road leading to the West Gate, West Bridge, and the river port in the central shopping district.

During the 11th century the tower was completed to its present height and a (lost) spire was constructed. The westernmost two bays of the south aisle and the south and now blocked western doorways also date to this phase of construction.

In in 1107 the parish was granted to the Canons of the College of St Mary de Castro and passed to Leicester Abbey on its foundation in 1143 remaining in its possession until the Abbey was suppressed during the Dissolution of the Monasteries.

In c. 1220 the dedication was changed to St Nicholas. The early dedication of the church is not certain, however a chronicle of Leicester Abbey mentions a church near the Forum dedicated to St Augustine and St Columba lost by the time of writing. However the chronicler is seemingly unaware of the dedication change at St Nicholas so it is reasonable to suppose both that St Nicholas Church was meant and that the dedication was original to the time of the Anglo-Saxon minster. The new dedication, Nicholas of Smyrna, the patron of sailors, merchants, and pawn brokers, was likely chosen because of the proximity of the Soar river port just west of the church and the parishes vibrant commercial life.

In the 13th century the church underwent expansion, creating most of the floor plan of the building we see today. The old apsidal east end was demolished and replaced with a new chancel stretching to the east of the tower. The south aisle was very significantly widened to create a prominent Lady chapel. To the north of the new chancel and sanctuary, east of the north transept, a chantry chapel was also constructed. After the reform of the chantries this chapel was demolished and has never been reconstructed leaving remnants of the piscina of exposed on the external north wall of the chancel. It is probable that this round of restoration was paid for by one wealthy benefactor, probably the key beneficiary of the chantry prayers, as the parish had become quite poor by the High Middle Ages.

In the late 15th century the nave roof was elevated to its present height and the clerestories put in. The south porch also dates to this period.

Reformation and Civil War periods

As in all of Leicester and England's parishes, life at St Nicholas was heavily impacted by the English Reformation, following First Act of Supremacy when Henry VIII declared himself Supreme Governor of the English Church. For St Nicholas the first consequences of this process were felt in 1538 during the Dissolution of the Monasteries when the nearby monastic houses of Austinfriars, Blackfriars, Greyfriars and the parishes patron, Leicester Abbey, were forcibly suppressed. At this point the parish advowson passed to the Crown which continued to present vicars to the parish directly until 1867. Within the parish church itself, the Chantry Acts of 1545 and 1547 meant for the end of the chapel in the north aisle which collapsed the following century and has never been replaced. St Mary de Castro also lost its ancient chantry function at this stage.

After Edward VI succeeded his father the Protestant nature of the reform intensified. The services of the church ceased to be celebrated according to the old Latin Sarum Rite when the First Book of Common Prayer and Book of Homilies was adopted by order of parliament. The parishes of Leicester also lost most of their ancient wall paintings, statues, and rood screens at this point. These reforms and those of Henry were then sharply overturned by the accession of Mary I to the throne when full communion with the Papacy and all ancient liturgical forms were restored. The Catholic Restoration did not outlive Mary I and the reforms of Henry and Edward reinstated with a revised Book of Common Prayer under Elizabeth I as part of the Elizabethan Settlement.

The Elizabethan Settlement remained in place until the time of the English Civil War at which point the Church of England was reformed to its most austere extent when the Directory for Public Worship was promulgated by parliament, until the return of definitive edition Book of Common Prayer in 1663 under Charles II. While there is no parish record of the various changes at St Nicholas there are for the neighbouring parishes of St Martin's and St Margaret's, which record in exacting detail the sale and purchase of the various changing ritual items and prayer books each stage of the reformation demanded. An old rumour suggests that during the period of the Commonwealth St Nicholas was the one church in the city that refused to obey the rebel parliament and maintained liturgy according to Charles I's Prayer Book.

Parish decline in the Early Modern period

In addition to these locally felt national events, St Nicholas and the wider Western Ward of the Borough of Leicester during the early modern period were marked by decline into greater and greater degrees of poverty and deprivation. For the parish this was largely due to the end of abbatial patronage following the dissolution of 1538, the end of chantry fund for the chapel in the north aisle and other Roman Catholic schemes for promoting regular donations, and a continued decline in the wealth of the parish population. This wider problem of poverty among the burghers of the Western Ward was a gradual trend predating the Reformation in which the focus of shopping shifted to the towns East Gates (now the area around High Street, Humberstone Gate, and Gallowtree Gate) still the focus of Leicester city centre today. Along with poverty there was also stagnation and decline in parish population with 120 residents in 1536 and just 90 by the beginning of the 18th century.

The upshot of poverty and population decline was decline in the fabric of the church. Sometime in the 17th century the north aisle collapsed. By this stage the chantry chapel had also disappeared, either through decline or by the deliberate choice of reforming iconoclasts. By the 19th century the tower had become so weak that the spire had been dismantled. When windows were broken they were bricked up because of a lack of money for glass.

Throughout the parishes history since the reformation there have been various attempts by local and national civic and ecclesiastical authorities to respond to St Nicholas's poverty. Around 1651–2, during the Protectorate of Oliver Cromwell, it was proposed to unite the benefices of St. Nicholas and St. Mary de Castro but the plan didn’t materialise. Two grants from Queen Anne's Bounty were made in 1714 and 1800 and two parliamentary grants in 1813 and 1824. The vicarage was additionally supported by various tithes paid by the Corporation of Leicester Borough. In spite of all these gifts, by 1831 the vicarage was worth only £35.

In 1789 William Carey became minister of Leicesters Particular Baptist congregation and took up residence in Thornton Street which was part of St Nicholas parish. He is regarded as a key founding figure in the global Protestant missionary movement, widely known as Father of modern missions. Carey's house was preserved as a museum until the mid 20th-century redevelopment around the site when, following much protest, it was demolished.

Victorian population growth

The population of the parish grew drastically during the 1700s from just 90 at the beginning of the century to 947 in 1801, reaching a high of 1'925 in 1871. By 1825 the fabric of the church was in such poor repair that Richard Davis, Vicar of St Nicholas, sought to demolish and reconstruct the parish church. The poverty of the parish meant he failed to raise the necessary funds. During this time the south wall of the old Anglo-Saxon nave including its ancient arches were pulled down to make way for a large brick arch between the nave and south aisle allowing more parishioners into the church at the cost of the Anglo-Saxon structure.

In the later Victorian period, between 1875 and 1884, the church was heavily renovated during which time the north transept and north west aisle, lost since the 17th century, were replaced. The bricked up arch in the eastern extern wall shows the project was intended to replace the chantry chapel with a vestry however after a hundred years of fundraising the project was abandoned in 1980. A new, now lost, reredos and high altar were installed during these late Victorian refurbishments. The pink granite facade of the south aisle also dates to this period.

Recent history

From the end to the middle of the 19th century the parish became increasingly industrialised and less residential. In 1931 the population of the ecclesiastical parish was 1,388 and in 1949 it was estimated to have fallen to about 1,000. The church in turn was impacted and by the end of the war faced a dwindling congregation. This trend was reversed when St Nicholas was made the ceremonial church and chaplaincy to the University of Leicester in the 1957. Although a long distance from the university it was chosen for its ancient character. A Sunday bus service known as the "Holy Bones Express" operated between the university and the church enabling students to reach it. Although this ministry wore off towards the end of the 20th century its spirit has continued in today's Inclusive Church and its predominantly young congregation.

A number of renovations were carried out in the 20th century bringing the church to its present condition. The stonework of the tower was restored in 1904-5. The Lady Chapel renovated in 1929 when the Atkins Window went in. In 1970 the exterior of the church was floodlit to celebrate the 750th anniversary of the 1220 rededication of the church to Nicholas of Smyrna. Dr Michael Ramsey, the Archbishop of Canterbury, visited on the Feast of St Nicholas (December 6th) the same year to conclude the festivities. In 1975 the floor of the choir and sanctuary were lowered, the south aisle repaved, and a 15th-century octagonal font from the redundant Church of St Michael the Greater, Stamford inserted to create a baptistry on the site of the south transept. The nave altar also dates to this period.

Present community

St Nicholas is the official ceremonial University Church for Leicester. It is a member of the Inclusive Church Network, with a mission to welcome people of diverse sexualities, identities, disabilities, origins, and socioeconomic situations. As a result, it has acquired a significant group of LGBTQ worshippers and prominently displays pride flags.

With its Sunday mass held at 6.30pm, it has a niche as Leicester's evening congregation, providing Anglicans in the city with their last opportunity to receive Holy Communion on a Sunday before Monday.

St Nicholas is one of, or the only, church in the UK to have an Ornithologist in Residence, Dr Alexander Bond, chief curator of the Natural History Museum at Tring.

Building

Materials

All of the materials for the 9th-century nave were recycled from materials used in the earlier Roman bath house and forum. These largely consisted of bricks and roof tiles but also included granite, limestone, sandstone, and slate. The 13th-century sections of the building are local limestone and recycled Roman remains. The 19th-century north aisle structure and south aisle fascia are pink granite.

The most notable of the recycled Roman objects in the church is the St Nicholas "paw print tile" visible in the north wall of the Lady Chapel. It is large section of Roman roof tile with an exceptionally clear paw print of a small dog, presumably made by a straying canine during the drying process. One of Leicester's most beloved relics of its Roman past, the tile provides a very tangible link to every day life in Ratae in the 2nd century.

Structure

The structure consists of a double bayed nave divided from a two bayed chancel by a central crossing tower, a double bayed north aisle ending at a transept, and a five bayed south aisle constituting a Lady chapel. The nave, dating before 879, is a stylistically Anglo-Saxon form of the basilica comparable to that at All Saints' Church, Brixworth. This was developed during the early 10th into a cruciform church centred around the tower in a form like that of Stow Minster. The south aisle, partly 11th-century, retains just a few of its Norman features. The romanesque stylistic unity was modified by the replacement of the original sanctuary and the addition of the Lady Chapel in the south aisle during the 13th century, both in an Early English style. In the 1820s the nave was severely damaged by the removal of its Anglo-Saxon south wall and its replacement with a single bay in a similar form to a railway arch. The structure was completed in the late Victorian period by the addition of the north aisle and transept with its bricked arch anticipating an unbuilt replacement to the chantry chapel.

Exterior

The exterior is typical English gothic with a few clues to the Anglo-Saxon core of the building. The east end is formed two gables of equal height facing the north entrance to the Vaughan Way Underpass, the exterior of the Lady chapel and chancel. The site of the chantry chapel is clearly visible on the north elevation of the chancel in the outline of its entrance arch, vaulted ceiling, and piscina, as is the intended Victorian extension in the bricked up arch in the east wall of the north transept, now the sacristy. The west elevation is obscured by the Jury wall but the hidden west end of the nave is mostly Anglo-Saxon work. The south elevation is punctuated by a humble 15th-century timber porch, four gothic windows with 19th-century restored reticulated tracery, a small priests door, and an 18th-century slate sundial. The sundial is dated 1738 and was placed in situ c. 1760. Of the visible areas of the exterior, only the lower levels of the tower hint at the Anglo-Saxon origin of the church with their herringbone pattern of Roman bricks and rustic blind arcading. The upper sections of the tower are Norman and has a clock face in the central upper arcade on the south and western faces.

South porch

The south porch was constructed of timber and brick in the late 15th or early 16th centuries at the same time nave clerestories and roof. Its most charming feature is the head of a small figure peering down on the visitor from the roof inside the porch. The porch conceals an early Norman doorway with a typical zig zag pattern around its archivolt which opens out into the south aisle.

The access from the porch to the church takes the visitor down several steps. This is because the ground level outside has risen significantly due to centuries of burials and the demolition of nearby property.

Nave

The central aisle or nave is the oldest section of the building dating back to the 9th century or before. When constructed it possibly extended a little further west to the Jewry Wall which it incorporated as a west front. Its form was basilical but rested on sturdy sandstone piers rather than slender columns. Today it is double bayed on the Anglo-Saxon north wall but single bayed on the south thanks to the demolition of the original arcade by the early Victorians when the population grew.

The northern arcade is the most complete surviving section of the original Anglo-Saxon minster. An exceptional survival, it is constructed entirely of rubble sourced from the ruins of Ratae. Its two arches are both surmounted by arched clerestory windows which now face into the heightened north aisle. They clearly consciously imitate the Roman building methods in the adjacent bath house complex with their double layering of recycled bricks. It is possible that they are older than the arches beneath and that these date to after the Danish invasion when the church was expanded. The nave was heightened in the late 15th century and its roof and new upper clerestories are typical of early Tudor gothic. Between the two clerestories the royal arms of George II is hung. It dates to 1746.

In the single bayed southern arcade only the western pier is ancient, the rest dates to 1829-30 when the ancient arcades were removed. The extremely unusual early 20th-century concrete and cast-iron pulpit is wrapped around the eastern pier of the south nave arcade so that the preachers can address the congregation in the south aisle.

Tower

The crossing tower dates to the 10th century, a time when the church was expanded to include transepts and aisles, and was probably constructed on the site of an earlier apse. It is without doubt the church's, and Leicestershire’s, finest surviving pre-Conquest structure. Consisting of four solid piers supporting large triumphal arches the walls both inside and out are decorated with blind arcade work forming three levels, one visible within and two from without. The tallest upper band of arcading where the bell chamber sits is a Norman addition dating to the late 11th or early 12th century. A key characteristically Anglo-Saxon feature is the herringbone brickwork visible from the external south elevation and inside the locked lower tower chamber.

In the Victorian era the tower was arranged as the choir, stalls were laid out facing one another in the usual way, and an organ was place in the north arch. This arrangement of the choir reflects medieval arrangements.

Chancel

The chancel extending beyond the east arch of the crossing tower is 13th century. Until the reconfiguration of the church to contemporary taste in recent times this area was the principle ritual heart of the building. It is probably the site of a 10th-century apsidal chancel constructed at the time of the tower. The current structure with built in the 12th century in an early English style. It was here that the Eucharist was celebrated through the Middle Ages on a lost high altar through the reformation till recent times. Today it remains a visual focus but is primarily used by musicians during Sunday services.

The chancels most striking feature is the charmingly crooked clustered column and the generally rather fine 13th-century decorated work of the south arcade separating the chancel from the Lady Chapel. In the north wall there was access to the lost chantry chapel through the now clearly visible blocked arch. The arms of the Mayor of Leicester are hung in the arch.

South aisle and Lady Chapel

The south aisle, like the nave, underwent many stages of construction, reconstruction, and restoration. Its oldest section is the western pier of the Victorian arch, the only surviving section of the Anglo-Saxon naves south arcade. This wall, facing the visitor on entry from the south porch, is the location of the "St Nicholas paw print" visible on a tile about two thirds of the way up the wall a little left of the middle. There has been a south aisle since at least the 10th century. The width of the present one was set by the Normans whose construction survives largely intact around the south door and west front.

The rest of the south aisle and its large stained glass windows date to the 13th century when the 10th-century south transept was demolished and a Lady chapel constructed at the east end. The priests door, triple sedilia, and aumbry all date to this phase like the arcade separating the lady chapel from the chancel. The sedilia, three adjacent niches set into the south wall of the Lady Chapel, were the seats of the priest and his two assisting deacons during the celebration of solemn masses. Such a feature, more usually associated with a high altar rather than a devotional side altar, suggests that the parish of St Nicholas was not immune to the very well developed cult of the Virgin Mary in medieval Leicester since it implies regular sung votive masses offered to her.

Today the south aisle remains a devotional area. It is the setting for the parish celebrations of the liturgy of the hours and various healing liturgies. The aumbry to the left of the sedilia, on the right hand side of the Lady altar, is where the Blessed Sacrament is reserved and the sacramental presence of Christ marked by a bracket with a burning lamp on the wall above. The 15th-century baptismal font, located in the central bay of the south aisle, was transferred from the redundant Church of St Michael the Greater, Stamford to St Nicholas.

North Aisle

The north aisle lies beyond the two ancient arches in the north wall of the nave. Constructed in the 1875-84 renovation from granite they provide an important view of the nave arcade and a home for the lavatory, sacristy, Sunday school, and tea making facilities.

Stained glass

The churches 5 principal stained glass windows are all in the south aisle and Lady Chapel.

The Children’s Window

The westernmost of the south aisle windows and set in the original 11th-century frame, this Victorian lancet window depicts the verse "Suffer the little children to come unto me" and was selected from a catalogue design. It is dedicated to the children of the Parish.

The Crane Memorial Window

A depiction of the raising of Raising of Jairus' daughter erected around 1886 by a local firm, Herbert and Gardiner, in the third bay of the south aisle from the west. It is dedicated to the memory of various members of the Crane family who had worshipped at St Nicholas, Joseph Wyatt Crane, his wife Janet, and their children Jessie, Helen, Blanche, Louise, and Edward. It was donated by their grandson, Alfred Wyatt Crane. The window is mentioned in University College London's Legacies of British Slavery Database. Although no member of the family personally owned any slaves, Joseph Wyatt Crane once acted as executor to the will of a slave owner.

The two Wakeford Memorial Windows

In the easternmost two bays of the south aisle are two windows dedicated to members of the Wakeford family.

The first one on the left, above the sedilia and overlooking the Lady altar, dates to 1898 and depicts the Blessed Virgin Mary, depicted holding a lily and a book, Saint Nicholas of Smyrna, the parish patron depicted holding a bishops crosier and his characteristic three nuggets of gold, and the figure of a crowned angel, possibly the Angel of Christian Charity. It is dedicated to the memory of the remarkable Elizabeth Threapland Wakeford. A graduate of the University of London and a respected mathematician, she moved to Hong Kong and became a teacher particularly devoted to the education of women. Like many missionaries she died young, just 37 year old, and was buried with her infant daughter Mary in Hong Kong. The window was paid for by Elizabeth's husband Edward Wakeford.

The second one on the left is dedicated to the sons of Elizabeth, George Tarik and Edward Kingsley Wakeford, who were both killed in action in 1916 during the Great War. It depicts the risen Christ still bearing the crown of thorns on his head and his wounds but holding a crown of victory in his left hand. Either side of him are St George to the left, a Roman soldier and the chief patron saint of England, and the Archangel Michael to the right, depicted bearing the sword of truth and the shield of justice.

The Atkins Memorial Window

The east window of the Lady Chapel in the wall behind the altar was erected in 1929 and depicts the Presentation of Christ in the Temple, including the figures of the Virgin Mary, St Joseph, and Simeon. The scene is set in the Temple at Jerusalem and an interesting feature are the two caged turtle doves in Joseph's hand, the sacrifice offered by poorer families in thanksgiving for a firstborn child. Beneath the scene of the Presentation are two crests, the arms of the City of Leicester on the left and the arms of the Diocese of Leicester on the right. Both shields contain the ermine cinquefoil of the De Beaumont Earls. The window is dedicated to the memory of Canon Edward Atkins, Vicar of St Nicholas, Leicester for 34 years between 1893 and his death in 1927.

Organ

The organ was built in 1890 by the local firm of J. Porritt, and incorporates pipework of an earlier organ by an unknown builder dating from the 1830s. In 1975, the organ was cleaned and overhauled by J. W. Walker & Sons Ltd at a cost of around £4,500, and has continued to be refurbished periodically since then.

Ian Imlay was the organist from 1960 until his death in August 2021.

Bells

The church has three bells, dated 1617, 1656 and 1710, that had been taken down from the tower in 1949 and replaced by one big bell. As part of the millennium celebrations, the three bells were rehung at a total cost of £5,848, paid for by an appeal. Because the tower is not very strong, they were re-hung for stationary chiming (not swung). The smallest bell, which was cracked, was repaired, and all three bells were taken away to Hayward Mills Associates Bell Hangers of Nottingham. They were returned to the church in July 2002, and were rung to welcome Queen Elizabeth II on her Golden Jubilee visit to Leicester.

References

- ^ "History of St Nicholas Church". Retrieved 25 January 2025.

- ^ McKinley, Richard (1858). A History of the County of Leicester. Vol. IV. London: Victoria County History.

- ^ "Church of St Nicholas". Historic England. 28 July 1997. Retrieved 28 January 2025.

- Ellis, Colin (1948). History in Leicester. City of Leicester Publicity Department. pp. 21, 24.

- ^ Hulme, Jay (2024). A Guide to St Nicholas Church Leicester.

- ^ "History". St Nicholas Church in Leicester. Archived from the original on 16 September 2022. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- "Welcome". St Nicholas Church in Leicester. Archived from the original on 16 September 2022. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- Hulme, Jay (9 September 2022). "The fall of a sparrow observed". churchtimes.co.uk. Church Times. Archived from the original on 16 September 2022. Retrieved 16 September 2022.