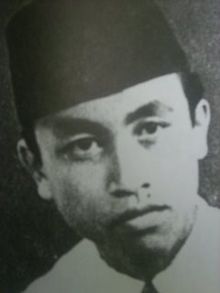

| Rosli Dhobi | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 18 March 1932 Kampung Pulo, Sibu, Kingdom of Sarawak |

| Died | 2 March 1950(1950-03-02) (aged 17) Kuching, Crown Colony of Sarawak, British Empire |

| Cause of death | Execution by hanging |

| Burial place | Kuching Central Prison Cemetery, Kuching (1950-1996) Masjid An-Nur, Sibu (1996-present) |

| Other names | Rosli Dhoby |

Rosli Dhobi (18 March 1932 – 2 March 1950) also Rosli Dhoby, was a Sarawakian nationalist from Sibu of mixed Malay-Melanau descent during the British crown colony era in that state.

He was a member leader of the Rukun 13, an active organisation in the anti-cession movement of Sarawak, along with Morshidi Sidek, Awang Rambli Bin Deli and Bujang Suntong. It was a secret cell organisation, composed of nationalists, which carried out assassinations of officers of the British colonial government in Sarawak. He was well known for his assassination of Duncan George Stewart, the second governor of colonial Sarawak, in 1949.

Early life and education

Rosli Dhobi was born on 18 March 1932 at House No. 94, Kampung Pulo in Sibu, as the second child cum elder son in a washerman's family. His father, Dhobi bin Buang was an ethnic local Sibu Malay who had ancestral roots in Kalimantan, Indonesia and was a descendant of Raden ranked nobles. His mother, Habibah binti Haji Lamit, came from a Sambas Malay family that was settled for a long time in Mukah which intermingled with the local native Melanau population. Rosli had an elder sister, Fatimah (1927–2019) and a younger brother, Ainnie (born 1934). Little is known about his early life although his friends regard Rosli as an approachable person despite his quietness. Rosli was soft-spoken, respects the elders, and humble. Rosli also had a girlfriend named Ani.

Rosli worked at the Sarawak Public Works Department (PWD).

In 1949, Rosli resigned from government service when the colonial government issued Circular No 9. At 16 years old, Rosli attended morning classes at a Methodist school as a standard 6 pupil. Rosli became a teacher at the Sekolah Rakyat Sibu religious school in the evenings.

Political activities

Rosli became a member and was appointed vice secretary of Sibu Malay Youth Movement (Malay:Pengerakan Pemuda Melayu, PPM) under the leadership of Sirat Haji Yaman.

In mid-1948, Rosli complained to Abang Ahmad Abang Haji Abu Bakar that the PPM top leaders were plotting to chase the white people away from Sarawak but didn't invite him to participate. Meanwhile, Abang Ahmad told Rosli that secrecy prevents the information from leaking to unintended parties. Rosli responded that he would rock Sarawak by giving a nice punch against the British colonial masters. Rosli later joined the top leaders of PPM in the establishment of a new organisation named Rukun 13 with Awang Rambli as the leader in the same year. In a meeting held at Telephone Road in Sibu, Awang Rambli stated that their previous protests did not bore any fruit during the last three years. Therefore, more radical action had to be taken such that the new British governor had to be killed. Rosli was selected to perform this task because he was still young and the British would not expect an assassination attempt by a young person. Awang Rambli also promised to help Rosli if the latter were to be thrown into jail later. After that, Wan Zen Wan Abdullah and Awang Rambli read a passage from al-Quran (Yassin). All the people who attended the meeting swore by drinking a glass of water in which they would not leak the minutes of the meeting to outsiders. If the promise is broken, they will be condemned greatly.

One of Rukun 13 aims was to establish a union of Sarawak with newly independent Indonesia. Sukarno, the first president of Indonesia was highly regarded by the Sarawak Malays. Posters of Sukarno were found to decorate Malay houses in Sarawak. Tahar Johnny, a cousin of Rosli, denied that Rosli was pro-Indonesia despite the latter taking a liking to anything Indonesian, and other members of Rukun 13 may have been pro-Indonesia.

By using the pseudonym Lidros, Rosli wrote a nationalist poem titled "Panggilan Mu yang Suchi" (Your Divine Call). The poem was published in a Malay newspaper named Utusan Sarawak on 28 February 1949. The usage of nicknames was prevalent at the time since the British Colonial Authority actively monitored any attempts that could undermine the stability of the government.

Assassination of Duncan George Stewart

On 2 December 1949, Yusuf Haji Merais and Abang Kess Abang Ahmad met Mostaffa Takip and Rosli Dhobi while they went to Rex Cinema to meet with a nobleman named Wan Wan San. Rosli brought them to Ibu Habsah's house where other friends such as Morshidi Sidek, Rabee Adis, Wan Ahmad were waiting in the house. In that informal meeting, they talk about their struggle and nationalism. When talking about the new governor Duncan George Stewart first working visit to Sibu tomorrow, Rosli stood up and said that he wished to kill the governor. However, all the people in that meeting did not believe in him because such a statement has been heard frequently from other young people during casual talk. After the meeting, between 9 and 11 pm, Rosli, Yusuf and other friends went to the Encik Aninie Sepet's house to watch people drumming. Just before 12 am, they went to the house of Yusuf Haji Merais at Kampung Pulo (behind Chung Hua school). Rosli requested to wear the Yusuf's festive clothes. After that, Rosli went back to his own home.

On 3 December 1949, Yusuf was awakened by Rosli at 4 am when latter knocked at his door. Yusuf handed over his identity card to be given back to the British and gave final advice to Rosli. At 6 am, Rosli went to Morshidi's house to discuss the planned assassination. Rosli bought a camera and a dagger. At 8 am, Rosli met Yusuf at Pacific Traders office at Pulo Road. Rosli requested forgiveness from Yusuf and wish that the struggle for Sarawak independence to continue. Rosli then went to Methodist primary school, standing in line to welcome the arrival of new British Governor Duncan George Steward. Rosli stood beside Morshidi and gave the camera to him. After inspecting the guarding of honour, the governor went to meet a group of schoolchildren. When the governor appears, Morshidi pretends to take a photograph of the governor so that the governor stops walking and allows Morshidi to take a photograph. Rosli then stepped out of the line, pulled out the dagger, and tried to stab the governor. His first stab missed the governor. When two police officers noticed Rosli and ran towards him, he threw the dagger towards the governor. Morshidi then pulled out his dagger and tried to attack the governor. However, Morsidi's attack was foiled by third-divisional resident named Barcroft and a confidential secretary of the governor named Dilks. Rosli was immediately arrested by the police. However, Rosli did not feel any regret for his actions.

Despite suffering from a deep stab wound, Stewart was reported to have tried to carry on until blood began to seep through his white uniform. Duncan Stewart was immediately rushed to Sibu Hospital and then Kuching Hospital on the same day. Dr Wallace planned for an emergency operation on the governor on the next day (4 December 1949) in Singapore. Duncan Stewart died on 10 December 1949, one week after the incident.

Trial and imprisonment

On 4 December, members of Rukun 13 were remanded and their houses were searched.

Rosli was initially tried for attempted murder. After the death of the governor, the charge was changed to murder. The hearing was done at Second Circuit Court, Sibu. Rosli did not want any defendant's lawyer on his behalf, while he stood trial on his own. Rosli questioned the witness on the following points: Firstly, when a Sikh police officer brought back the dagger, he left his thumbprint on the dagger. There was no witness to say that Rosli had stabbed the governor. Secondly, Rosli argued that the governor did not die immediately after the incident but after the Dr Wallace's operation. This implied that Dr Wallace was the killer instead of Rosli Dhobi. Rosli successfully defended himself on these points.

However, Barcroft and Jerry Martin met the mother of Rosli later and asked his mother to persuade Rosli to plead guilty to reduce the severity of punishment for Rosli. After his mother's persuasions, Rosli decided to plead guilty. Rosli was found guilty and was sentenced to capital punishment by hanging to death. This is also the first capital punishment in Sarawak.

While Rosli was imprisoned, he diligently recited surah Yassin from al-Quran. He did not talk much. Just before his death, Rosli gave a few advice to his friends and wrote letters to his family members.

Death

After a few months languishing in Kuching prison, Rosli Dhobi (or Dhoby), Awang Ramli Amit Mohd Deli, Morshidi Sidek, and Bujang Suntong were found guilty of murder and sentenced to death. This move was criticised by many, as Rosli was a juvenile (17) at the time of assassination.

Before Rosli's hanging, Abang Haji Zaidell (father to Datuk Safri Awang Zaidell) gave an anesthetic injection to Rosli. Rosli reportedly told Awang Mois that (in Sarawak Malay language) "Keadaan kita tok, ada hidup ada mati. Keakhirannya ngine pun, kita mati juak. Enta saya, entah kitak... betermulah!" (Our situation has life and death. No matter what is the outcome, we die anyway. I or us, ... just face it!) Rosli last words to prison officers was "Apabila saya hendak digantung kelak, tunggu saya habis membaca kalimah." (Before I am hanged, wait for me until I finished reciting the kalimah. His wish was granted by Westin, an Englishman posted from Changi prison in Singapore.

Rosli was subsequently hanged together with Morshidi on the morning of 2 March 1950 at the Kuching prison. Fearing the resentment of the local population, the British government did not allow the bodies of the four assassins to leave the Kuching prison but were interred in unmarked graves within the prison compound. After Sarawak joined Malaysia on 16 September 1963, a tombstone was put in place at his grave near the Islamic Heritage Museum.

Aftermath

Sarawak was sent into tumultuous years, and the anti-cessionists' rebellion was crushed as the support by the locals dwindled due to Rukun 13's "aggressive" tactics, alongside opposition from some of the Malay leaders who were pro-British. Most of the anti-cessionists were arrested and later sent to prison, some in Changi Prison in Singapore. Peace was restored during the era of the 3rd Governor of Sarawak, Sir Anthony Foster Abell. Even those who were imprisoned at Changi were allowed to return to Sarawak, to continue their sentence at Kuching Central Prison.

In 1961, Tunku Abdul Rahman, the prime minister of Malaya at that time, was trying to promote his plan for the formation of greater Malaysia in Sibu. He became interested on the story of Rosli Dhobi (or Dhoby). Tunku then discussed with chief minister of Sarawak, Abdul Taib Mahmud, to build a heroes monument near the Sarawak State Museum. On 29 November 1990, the laying of foundation stone for the heroes monument was done by Tunku and Taib Mahmud. Apart from Dhoby, other individuals such as Datuk Merpati Jepang, Rentap, Datuk Patinggi Ali, as well as Tunku Abdul Rahman, were hagiographed here.

In 1975, Mahathir Mohamad, minister of education at that time, changed the name of SMK Bandar Sibu to SMK Rosli Dhoby in commemoration of Rosli Dhobi.

After 46 years, Rosli's remains were moved out of the Kuching Central Prison to be buried in the Sarawak's Heroes Mausoleum near An Nur Mosque in his hometown of Sibu on 2 March 1996. He was given a state funeral by the Sarawak government.

In 2009, Malaysian television provider Astro screened a miniseries titled Warkah Terakhir ("The Final Letter") which described the story of Rosli Dhoby. The miniseries was produced by Wan Hasliza with actor Beto Kusyairy portraying Rosli Dhoby. However, Dhoby's relative, Lucas Johnny, said the series contained several factual errors. For example, the miniseries portrayed Dhobi as trying to run away after stabbing the governor. In reality, Rosli tried to stab the governor a second time but was stopped by the governor's bodyguards.

In 2012, a declassified document from the British National Archives showed that Anthony Brooke had no connection with the assassination of Stewart and that the British government had known this at the time. The British government decided to keep this information a secret as the assassins were found to be agitating for union with newly independent Indonesia. The British government did not want to provoke Indonesia which had only recently won its war of independence from the Netherlands, as the British was busy dealing with the Malayan Emergency.

Research

From 1949 to 1996, the Sarawak public generally regarded the struggle of Rosli and Rukun 13 negatively as a "bad guy", "imposter", and "rebel". Only after Sarawak state government gave a formal state funeral to the executed rebels in 1996 did public perception start to change. There are limited primary records regarding Rosli Dhobi (Dhoby) and other Rukun 13 members did not document their experiences publicly. The last Rukun 13 member died in 2009. However, several of the Pergerakan Pemuda Melayu (Young Malays Movement) members were still available in 2009.

Deputy director of Sarawak state prison, Sabu Hassan, in a formal reply written to Nordi Achie, a researcher working at Centre for the Promotion of Knowledge and Language Learning, Universiti Malaysia Sabah, stated that Malaysian prison department did not keep any record and files for the four offenders while a portion of the documents were destroyed by the British during the colonial times.

In 2013, Jeniri Amir, a professor from Universiti Malaysia Sarawak specialising in political communication, wrote a book about Rosli Dhobi which included new information. According to a review by Nordi Achie, Jeniri's book contained errors with only a superficial analysis of newly found information regarding Stewart's assassination.

See also

- Anti-cession movement of Sarawak

- Rentap, an Iban warrior who fought against Brooke

- James W.W. Birch, first Perak resident who was killed by Dato Maharajalela Lela

References

- ^ Amir, Jeniri (14 September 2016). "Rosli Dhoby: Merdeka dengan darah (Rosli Dhoby: Independence through blood)". Sarawak Voice. Archived from the original on 17 February 2020. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

- ^ Haji Khalik, Rudi Affendi (1997). Rosli Dhobi di Tali Gantung (Rosli Dhobi on the hanging rope) (First ed.). Kuching, Sarawak: Gaya Media Sdn Bhd. pp. 63–72. ISBN 9839373129. Retrieved 19 January 2025.

- ^ Thomson, Mike (14 March 2012). "The stabbed governor of Sarawak". BBC News. Archived from the original on 7 February 2021. Retrieved 17 February 2021.

- ^ Jeniri, Amir (2013). Rosli Dhoby: merdeka dengan darah (Rosli Dhoby: Independence through blood). Sarawak, Malaysia: Jenza Enterprise. pp. 11, 257–262, 264. ISBN 9789834337568. Retrieved 8 April 2021 – via Google Books.

- ^ Winston, Way (16 September 2013). "'They lied, Rosli Dhoby not pro-Indonesia'". Free Malaysia Today. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- Abg Mohd Nizam, Abg Nasser (15 July 2016). Pemberontakan Rosli Dhoby Terhadap Penjajah Inggeris di Sibu Sarawak (Rebellion of Rosli Dhoby against English Colonisers in Sibu Sarawak) (undergraduate). Faculty of Culture and Humanity - Sunan Ampel State Islamic University Surabaya. Archived from the original on 6 July 2019. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ Ian, Stewart (4 March 1996). "Sarawak honours governor's killers". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 4 April 2021. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- ^ Amir, Jeniri (2 March 2021). "The execution of Rosli Dhoby retold". New Sarawak Tribune. Archived from the original on 2 June 2021. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- Adawiyah, Rabi Atul (11 September 2014). "Jiwai semangat Rosli Dhoby (Emulate the spirit of Rosli Dhoby)". Harian Metro. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- "Discovering Sibu Historical Attractions". Sarawak Tourism. 24 September 2012. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- "Waris kecewa drama Rosli Dhoby salah fakta. (Heir was disappointed because Rosli drama is factually inaccurate.)". Malaysiakini. 10 September 2014. Archived from the original on 28 February 2018. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- Thomson, Mike (14 March 2012). "The stabbed governor of Sarawak". BBC News. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- "Document". BBC Radio 4. 12 March 2012. Retrieved 15 September 2022. - ^ Achie, Nordi (2018). Rosli Dhoby dan Rukun 13 (Rosli Dhoby and Rukun 13). Kuala Lumpur: University Malaya Press. pp. ix, 6–8. ISBN 9789831009536. Retrieved 24 December 2022.

- Nordie, Achie (2013). "Analisis Kritis dalam pensejarahan ilmiah - satu penyelitian terhadap "Rosli Dhoby - Merdeka dengan darah"" [Critical analysis in scientific historiography - research on "Rosli Dhoby - Independence through blood"] (PDF) (in Malay). Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 November 2017. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

Sources

- Adapted from Sabah dan Sarawak Menjadi Tanah Jajahan British, Sejarah Tingkatan 3 textbook

- Adapted from Pembinaan Negara Dan Bangsa Malaysia, Sejarah Tingkatan 5 textbook; ISBN 978-983-62-7883-8

- 1932 births

- 1950 deaths

- People from Sarawak

- Malaysian people of Malay descent

- History of Sarawak

- Melanau people

- Malaysian rebels

- Executed Malaysian people

- People executed by British Sarawak by hanging

- Malaysian people convicted of murder

- Malaysian assassins

- Nationalist assassins

- 20th-century executions by the United Kingdom

- Executed assassins

- Assassins of heads of government

- People from British Borneo

- Executed children